Community memory

Happy Labor Day. I wrote a Wikipedia article about the gay, anarchist, anti-profit publishing collective Come!Unity Press after stumbling across a poster they printed in 1971.

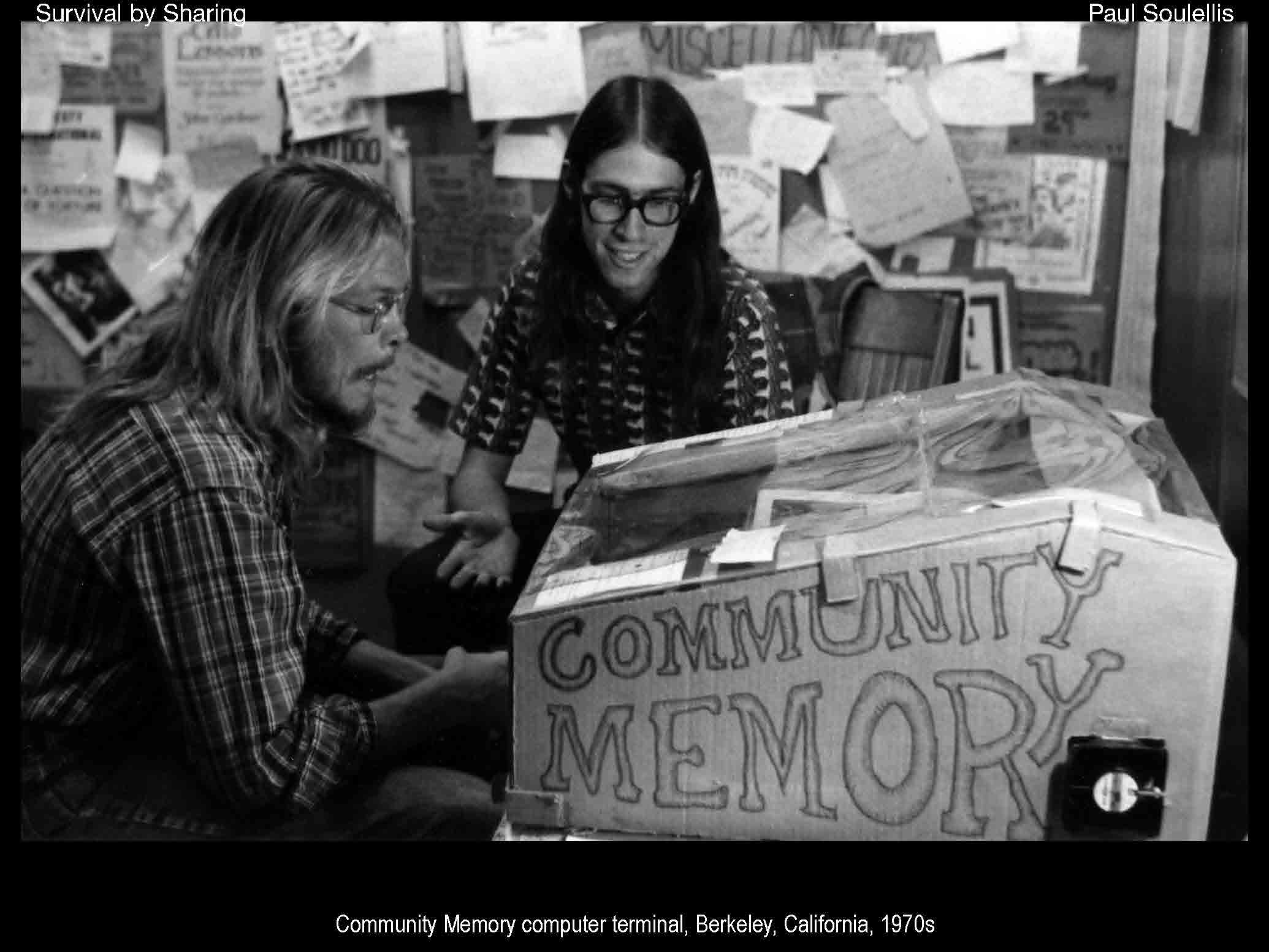

Serendipitously, while researching this article I came across a March 2024 talk about “Survival By Sharing” by Paul Soulellis , which features a photograph of a Community Memory terminal.

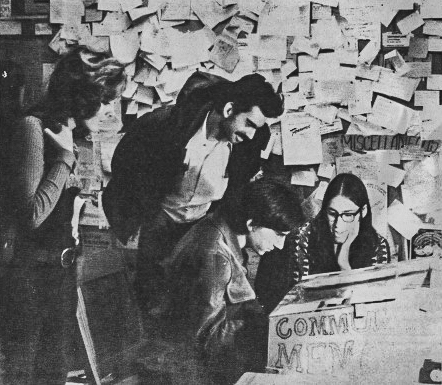

I'd come across some photos of these while looking for public domain photos of computers a couple weeks ago, and was disappointed at the time that I couldn't find a better photo than ones like this on Wikimedia Commons (derived from a scan of a 1974 newsletter):

Soulellis’ talk, however, features a much better photo of this very same terminal at Leopold's Records in Berkeley, CA, likely taken at the same time based on the outfit of the person featured in both shots!

The talk, which focuses on community and archives and collaborative art and resistance, has some really interesting throughlines with some of the things I’ve been thinking a lot about lately.

The Signal Journal of International Political Graphics and Culture published an interview with an early member of the C!UP collective in issue 5. You can borrow a copy for free from the Internet Archive. I was curious how the anarchists went from operating a printing press for a group of Quakers in exchange for free rent to running the whole shop. Turns out it came down to conflicts over topics including their nudism and a "political prisoner" (kitten) named Kropotkin. Signal recounts the story.

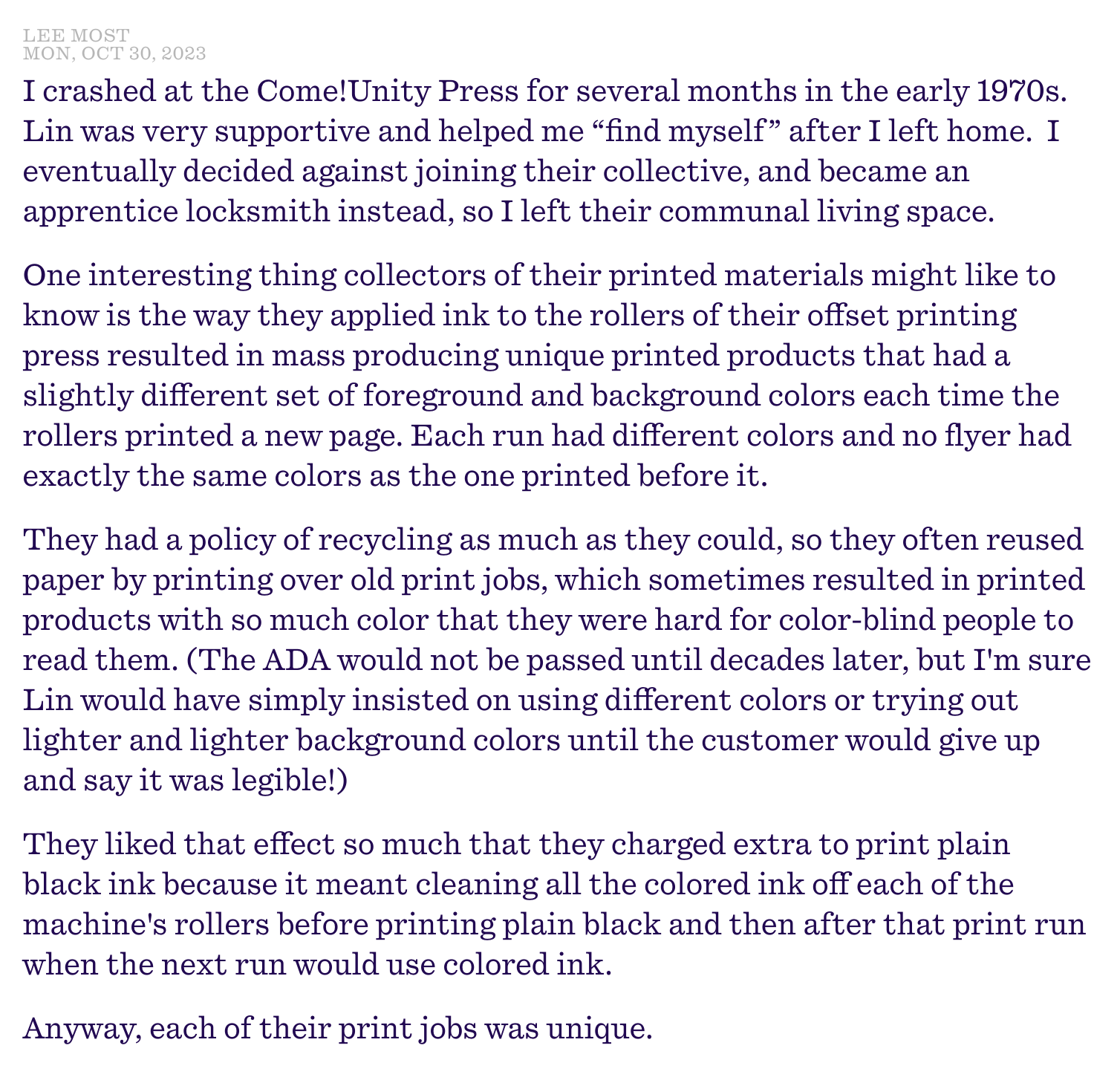

There’s another story from an early member of the collective to be found in the comments of a site called The People’s Graphic Design Archive: “They liked th[e rainbow ink] effect so much that they charged extra to print plain black ink”.